Best practices for facilitating Periscope lessons for TA/LA training or faculty PD

Select the Periscope lessons that meet your needs.

Select the Periscope lessons that meet your needs.- Plan 30-45 minutes of class time for each lesson.

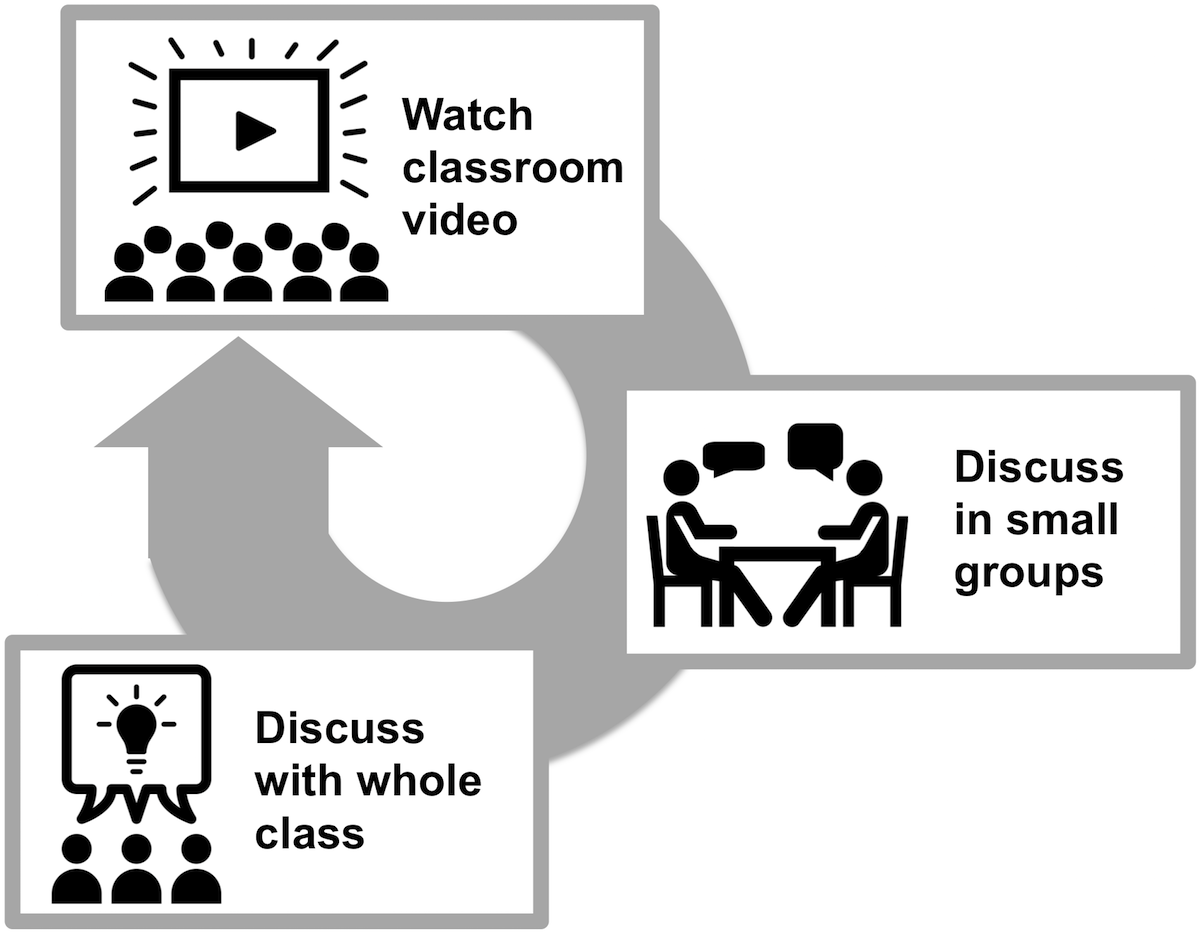

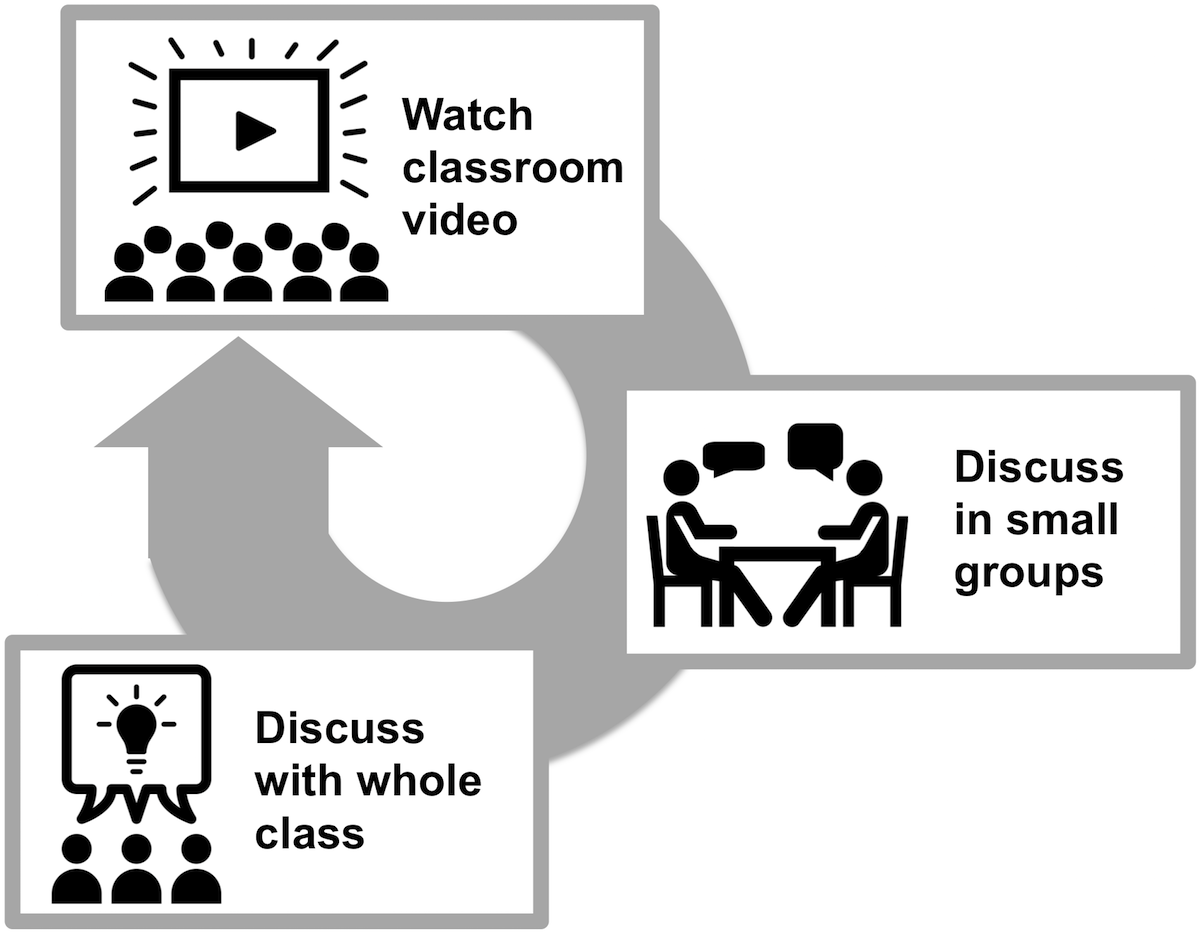

- For each lesson, do at least two cycles of communal viewing, small-group discussion, and whole-class discussion.

- Each cycle of viewing and discussion should be focused on a particular question or prompt.

Periscope connects authentic video episodes from best-practices physics classrooms to big questions of teaching and learning. Periscope lessons are useful if you:

- supervise learning assistants (LAs) or teaching assistants (TAs)

- lead faculty development

- seek to improve physics teaching in your department

- want to improve your own physics teaching

Periscope’s primary aim is to help physics instructors see authentic teaching events the way an expert educator does – to develop their “professional vision” (C. Goodwin, American Anthropologist 96(3), 1994). This development of professional vision is particularly critical for educators in transformed physics courses, who are expected to respond to students’ ideas and interactions as they unfold moment to moment.

By watching and discussing authentic teaching events, instructors:

- enrich their experience with noticing and interpreting student behavior

- practice applying lessons learned about teaching to actual teaching situations

- train to listen to and watch students in their own classrooms by having them practice on video episodes of students in other classrooms

- become aware of diverse perspectives on classroom events

- learn to notice and interpret classroom events the way an accomplished teacher does

- observe, discuss, and reflect on teaching situations similar to their own

- develop pedagogical content knowledge

- support their identities as teaching professionals

- get a view of other institutions’ transformed courses

- expand their vision of their own instructional improvement

Periscope is free to qualified educators at physport.org/periscope.

Each Periscope lesson includes the following materials:

- A one- to five-minute video episode

- A handout linking the episode to big ideas in teaching and learning, including:

- a question about teaching and learning (e.g., “How can I bring out student ideas?”)

- a description of the video episode for that lesson

- the physics task the students in the episode are working on

- transcript of the students’ conversation

- sample discussion prompts linking the episode to the lesson topic

- A lesson guide, including:

- sample sentence with which to introduce each video episode

- objective of the lesson

- common responses participants have

- the answer to the physics task the students are working on

The Periscope website offers a wide variety of lessons on numerous topics. Select lessons that meet your needs.

- There are collections of lessons that all address a common theme, such as “Productive group work” or “Student ideas.”

- The Physics Content, Pedagogy Content, and STEM-wide filters may help you find what you want.

Periscope lessons are designed for use in a classroom setting that alternates whole-class discussion with small-group discussions in groups of 2-4. The main part of a Periscope lesson is cycles of

- watching the video episode as a whole class

- discussing a question or prompt about it in small groups

- having groups report the results of their discussions to the whole class

Each cycle should last 10-20 minutes, and there should be a minimum of 2 cycles. Therefore, you should schedule a minimum of 30-45 minutes for a single lesson.

- Make sure your classroom has the proper facilities for playing video (with audio) to the whole class. Showing the video on a large screen to the whole class is technically simpler than having participants watch it on their individual computers.

- Prepare a copy of the lesson handout for each participant (print two-sided and in color, if possible). Participants will use these to refer to the task for students, the transcript, and the discussion questions.

- Review the lesson guide for each lesson that you use.

- Plan in advance what discussion prompts or prompting techniques will best suit your circumstances. Though there are sample discussion prompts on each handout, these are only one possible source of prompts.

You can use Periscope lessons for self-study by watching the video episode and reflecting on the sample discussion prompts. In this case, print out the handout so that you can easily refer to it while watching the episode, or open both the episode and the handout on a large screen.

The first time you use a Periscope lesson with a particular group of participants, explain to them why you will be using video of best-practices classrooms from around the country to help them learn about big issues in teaching and learning. Here are some possible reasons:

- Periscope episodes show diverse, intimate examples of what best-practices physics teaching really looks like at several different institutions around the country.

- Periscope episodes help you feel like you are really there for a moment in teaching and learning, sometimes more so than a live observation; this sense of being in on the action gives insight into what happened and why.

- When we all watch the same teaching and learning event together, we learn which of our observations and interpretations are universal and which are unique.

- When we watch the same teaching and learning event more than once, we can test our initial intuitions against evidence in the episode.

- When we discuss teaching and learning events together, we learn about the principles and values that motivate us as instructors and as students.

- Periscope lessons help us practice noticing and interpreting what happens in real teaching and learning events, training ourselves to notice and interpret what happens in our own classrooms.

- Periscope lessons help us practice applying broad principles of teaching and learning to specific moments in specific classrooms, without any students being harmed in the process.

Expect expression of values

Discussions about teaching often involve values that run very deep for the participants. Maintaining a respectful and safe atmosphere is crucial not only for developing a learning community among your participants, but also for enabling your participants to identify and share their values, examine them thoughtfully, and consider other possible perspectives.

Establish an agreement

The first time you use a Periscope lesson with a particular group of participants, you might want to establish an agreement such as one of the following:

- Strive to characterize what’s going on in the episode according to the people in it. Describe events in a way that the participants themselves would likely agree with if they were present.

- Limit discussion to what we see happening in the episode (observable evidence) and what we think it means (evidence-based interpretation). Set aside opinion, judgment, and critique.

- Recognize that while we will likely all agree on observations (e.g., “The LA never spoke”), and we may persuade each other of interpretations (“Those two students have the same idea”), value statements (such as “The LA should not have done that”) are personal: they provide an opportunity to learn about the person speaking, and may reveal commitments and priorities that are not universally shared.

1. Summarize lesson

Each time you start a new Periscope lesson, give participants a sense of what the lesson will be about. This information is summarized in the lesson title and introduction. You might also share the lesson objectives with them: these are stated in the Lesson Guide for each specific lesson. This should only take a minute.

2. Do “Task for Students”

Explain that you will be watching a video episode together of students who are working on the “Task for students” that is reproduced in the box on the handout. Have participants answer the “Task for students” themselves and discuss the right answer with each other. That way they start watching the episode with a sense of what the students in the episode are thinking about.

Participants can spend very little time or a lot of time on the “Task for Students,” depending on their background. Decide how much time you want them to spend on the physics question vs. discussing the teaching issues in the episode. We usually try to keep the time for the “Task for students” down to five minutes or less.

A correct answer to the “Task for students” is in the Lesson Guide for each lesson.

The main part of a Periscope lesson is a 10-20 minute cycle of communal viewing, small-group discussion, and whole-class discussion that repeats at least twice. Each cycle of viewing and discussion should be focused on a particular question or prompt.

The first stage of each cycle is for the large group to watch the episode together.

- Tell participants to watch the captioned episode rather than following along with the transcript, so that they can see the action as well as hear what is said.

- When you start the episode, say something simple such as “Okay, let’s watch,” without any special instructions.

We recommend communal viewing rather than having individuals watch the episode on separate screens, because

- it is technically simpler

- it gets the whole group thinking about the same event at the same time

The second stage of each cycle is for small groups of 2-4 participants to discuss what they saw in the episode. Small-group discussions:

- give all individuals a chance to process their immediate reactions to the episode

- help participants focus their observations on the specific prompt, if there was one

While participants talk to each other, you may:

- participate in a small-group discussion

- float to different groups and listen in

- just wait

After 1-5 minutes (depending on the schedule and the richness of participants’ discussions), transition from small-group to whole-class discussion with a sentence like, “Okay, I’m interested to hear what you observed.”

Alternatively, try having participants write individually in response to the prompt before small-group discussion. This can give people with a different interactional style the opportunity to respond in a different way.

The third stage of each cycle is a whole-class discussion. The purpose of the whole-class discussion is to:

- expose participants to observations and interpretations that had not arisen in their small group

- (in some cases) to build consensus about a question or prompt

The following general guidelines may be useful for facilitating whole-class discussions:

- Encourage participants to ground their statements in evidence from the episode. For example, when a participant says, “Great group dynamic,” you might say, “What do you see that makes you say that?”

- Encourage participants to respond to each other and let the discussion develop. e.g., “You see Deb as doing a thought experiment. Is that how other people interpreted line 15?”

- Revoice participant contributions, i.e., say in your own words what you heard a participant saying. For example, if a participant says, “They have the idea that electrons jump from one tape to the other,” you might say, “You see them talking in terms of a transfer of electrons.”

- Stay aware of when participants are making claims and inferences so that you can help them stay connected to the evidence. Claims and inferences can be welcomed, but identified – as in, “You’re thinking that Caleb is the only one to use scientific vocabulary. That’s a claim. Did anyone else make any observations about that?” or “You see Deb as being the leader. What observation led to your making that inference?”

- As you listen to and revoice participants’ contributions, see if you can recognize issues relevant to the lesson question, or if the participant is raising a new issue. For example, “You saw Deb disagreeing with Bridget. What ideas does each of them have about electrostatic charge?”

- When there’s a lull in the talk, you can always say, “What more did you see?”

The complete cycle (communal viewing, small-group discussion or writing, large-group discussion) should repeat at least once, usually with a different prompt each time.

With more than one cycle of viewing, participants experience seeing different things in an episode than they saw the first time or reconsider inferences that they had made. Both of these experiences are important for the development of professional vision.

Each cycle of viewing and discussion addresses a particular question or prompt. There are many possible sources of questions and prompts to stimulate discussion of Periscope episodes. The first prompt, however, should always be completely open-ended.

We have found repeatedly that participants cannot focus on a specific question about a video until they have had a chance to process what they have seen in their own way. Thus, after the first time you watch the episode with participants, use a very open-ended prompt such as one of the following:

- “What did you notice? Talk to your neighbor about what you noticed.”

- “What did you observe? Tell your group what you saw.”

- “What struck you? Talk to the person next to you about what stuck out.”

Benefits of open-ended prompt

An open-ended prompt has the special benefits of

- helping facilitators learn about the participants

- helping participants learn about one another

Different audiences will tend to focus on different aspects of the episode, such as:

- the physics ideas

- the instructional format

- the group interactions

- issues of equity and inclusion

Facilitators can also gain a sense of participants’ interests and expertise from their responses to an open-ended prompt, including their expertise with:

- best-practices instruction

- video analysis

- physics content

These natural interests and areas of expertise or development can shape the rest of the discussion.

Example responses

For example, in response to the episode titled “Jump up”:

- Some participants are impressed with the students’ persistent questions and efforts to construct a model.

- Others see the students as off-task, since the questions they are addressing are not on the worksheet.

- Some participants are concerned about the model that this group seems to arrive at, since it has incorrect features.

- Some participants especially notice the students’ gestures, or the gender dynamics, or the fact that some of them don’t finish their sentences.

A prompt for the second cycle of viewing, and subsequent cycles, should focus participants’ attention on a particular issue or question. The lesson question (which is the title of each lesson handout) makes a good second prompt, along the lines of, “Let’s watch this again, and this time I want you to think about the students’ electrostatics ideas.”

Connection to open-ended prompt

Sometimes, the things that participants share in response to the first (open-ended) prompt pertain to the lesson question. If that is the case, we suggest you try to use their comment to segue into the lesson question. For example, if a participant notices Bridget’s statement about an “equal distribution of pluses and minuses,” you might ask, “What does that suggest about her model of electrostatic charge?”

Another source of prompts is the “sample discussion prompts” printed on the lesson handout. Usually there are more sample prompts than you would use in a single session. A facilitator using a handout prompt would transition from the whole-class discussion of the previous prompt by saying something along the lines of, “Take a look at question 3 on the handout: ‘Caleb proposes a mechanism for how charge gets from one object to another. What is the mechanism that he proposes?’ Let’s watch the video again, and this time see what you observe that addresses that question.”

Benefits of handout prompts

There is great value in getting different groups to share their responses to the same prompt. We designed these prompts to have more than one very reasonable answer – sometimes even opposite reasonable answers. We prefer these kinds of prompts because:

- they seem to be more inviting to participants

- they reflect the real complexity of teaching and learning events

We hope that different participants will see the events in the episode differently, perhaps even taking different sides on a question. Subsequent viewings may either develop consensus or affirm distinctive viewpoints.

Alternatively, sometimes when we run a large class, we subdivide the class, assigning different small groups to different prompts. This covers more territory in a shorter time.

Risks of handout prompts

A risk with using the sample discussion prompts on the handout is that sometimes participants treat the handout like a worksheet, jotting down short answers and moving on to the next question. If you find that this is happening in your class, you might prepare a different handout for participants without the sample prompts on it. (All handouts are editable.) In this case you might choose to print a different copy of the sample prompts out for yourself only, to keep at hand during the discussion. Sometimes when we run a class this way, we give copies of the questions to the participants at the end of the session.

Organize prompts

Another source of discussion prompts is questions and issues raised by the participants themselves. To organize prompts generated in class:

- Write participants’ contributions on the board as they make them.

- While you are writing, refrain from response, judgment, or follow-up questioning.

- Once you have a list of contributions on the board, look it over. Choose (or co-choose with the participants) which contribution(s) to discuss in greater depth.

- Use your chosen contribution as the prompt for the next round of viewing.

Classify prompts

You may find it valuable to classify (and lead the group in classifying) the contributions that you write on the board into categories. Some frequently useful categories are questions, observations, claims or inferences, and value statements.

- Questions provide natural prompts for future cycles of viewing and discussion.

- Participants are likely to all agree on observations, but there may be an opportunity to make more detailed observations about a particular thing (e.g., Was the LA still there when Alanna said that? What gesture did Ben make right after? What was Alicia’s expression when Cass said that?).

- A claim (e.g., “Bella uses everyday language,” “Arianna is surprised”) is likely to be a useful prompt for the next round of viewing: participants can watch for evidence that supports or refutes the claim. Claims and counter-claims often appear in the same list and can be investigated in the same round of viewing.

- Value statements (such as “The LA should not have done that”) are personal: they provide an opportunity to learn about the person speaking, and may reveal commitments and priorities that are not universally shared.

Inquire into prompts

Often, participants find themselves having markedly different responses to the same events. Distinguishing among observations, claims, and value statements is useful for providing participants with alternatives to their gut reactions. For example, identifying a particular contribution as a claim can help to transform it into an object of inquiry: participants become willing to

- gather evidence pertaining to it

- muster competing arguments

- change their minds, even about positions that had initially been strongly held

Often, participants conclude that the evidence does not support a clear conclusion, which can be illuminating in itself.

Benefits and risks of prompts generated in class

We have seen participants have transformative experiences in which they recognize that a certain way they had been interpreting an event is central to their implicit theory of teaching and learning. For this reason, this discussion format is a favorite of ours, especially with experienced participants. However, it also takes the greatest investment of time at the start of a cycle. With many audiences, we elect to use a lesson question or handout prompt instead.

Another class of prompts is especially worthwhile for relatively advanced inquiry – when the lesson objectives have already been achieved, or with a particularly experienced group. The following general prompts can lead to increased insight about any episode.

Focus on single channel of communication

Prompt participants to narrow their focus by attending to only one “channel” of communication, such as:

- only gestures

- only prosody (the music of the voice)

- only facial expressions

- only body movements

You might ask each participant or each small group to select a different channel.

Focus on single participant

Prompt participants to take the perspective of a single student in the episode – to try to live through the episode as that person, foregrounding what they say, see, and do in their attention. You might ask each participant or each team to select a different focal person.

Yes, these are real (not staged) episodes of student learning; they are ordinary events in best-practices physics classrooms. Video is contributed to Periscope by home institutions that do their own video recording for the purpose of researching physics learning. Students have all consented to video documentation of their work and are in that sense aware of the cameras, but they normally do not attend to the fact that they are being recorded.

Periscope video is contributed to Periscope by physics programs that video record classrooms for their own reasons, typically for research. These programs collect the video ethically under supervision of their own institutional review boards. People who appear in Periscope videos have consented to have the video shared with educators. They have not necessarily consented for their video to be shared with the public. Therefore:

- You may share Periscope videos with faculty, teaching assistants, learning assistants, and other instructors.

- You may show Periscope videos at professional meetings for educators, such as meetings of the American Association of Physics Teachers.

- You may not show Periscope videos publicly or post them publicly online, e.g., as unprotected YouTube videos or on your publicly accessible class website.

Download a pdf version of this Periscope Facilitator's Guide

Add a Comment

Add a Comment